Behind each of your knees there are rigid cords of tendon running down each side, with a deeper fleshy hollow between them. These tendons are referred to as “hamstrings,” and they connect large muscles on the thigh’s backside to the lower leg bones. And when those muscles contract, these tendons transfer force from muscle to bone and make the knee bend. These tendons are very useful in life.

But they are also useful after death. The hindquarters of animals have the same tendons, and I learned in childhood that the term “hamstring” supposedly comes from the fact that these tendons are used to hang hams for curing. But is that true?

What is a Ham?

Whether you call it ham, prosciutto, speck, or jamon iberico, it is all the same thing: the cured thigh of a pig. Usually the entire hindquarter is cured, but the large majority of edible flesh comes from the thigh, where some of the body’s largest muscles reside (the same muscles connected to the stout hamstrings). The same cure could be applied to the hindquarter of any animal, though pigs are the most common.

Curing hams is an ingenious way to store a large amount of meat from a freshly killed animal. The basic recipe is to salt the hindquarter and hang it in a cool dry place where it will last for months without spoiling. Ancient humans figured out that this preservation method not only preserves meat but makes it unimaginably more delicious. This is one of many examples where functional food preservation also enhances flavor, and it is the reason that we still cure hams today instead of just throwing hindquarters into a freezer.

Virginia is known for its hams, and in the early 20th century many people said that if it doesn’t come from southern Virginia along route 1, it isn’t a real ham. In that region, pigs at the time ate a lot of peanuts which gave their hams a unique and delicious flavor. And months of hardwood smoke enhanced it further. Southern Virginia hams, according to a writer in the 1930s, have meat the color of Cuban mahogany and fat the deep transparent gold of amber [Kurlansky].

Why the Hindquarter?

What about the forequarter? Why can’t it also be prepared like a ham? The answer is: it can, but hindquarters are the most commonly “hammed” body part for two reasons: 1) they contain a large proportion of an animal’s total muscle mass, and 2) the geometrically tidy shape of the femur bone inside the thigh makes for easy slicing of the final product. An animal’s shoulder and upper arm would be much harder to slice due to the shoulder blade, the most oddly shaped bone in the body. But @chefswild on Instagram still cures a deboned and rolled shoulder.

Why Pigs?

While you can cure meat from virtually any body parts from any animal, pigs most commonly have their hindquarters cured for two main reasons: 1) Their size is just right. Cattle hindquarter can weight up to 200 pounds, and lifting them to hang from rafters would cause too many hernias and too many broken rafters. And the legs of smaller animals would dry out too quickly. 2) The leg fat between and surrounding a pig’s leg muscles is abundant, but also uniquely delectable. While the fats of many animals are waxy and unpleasant to eat (especially when chilled they leave a tenacious coating inside the mouth), cold pig fat, such as in ham slices, is silky and delicious.

So, Are Hams Hung from the Hamstrings?

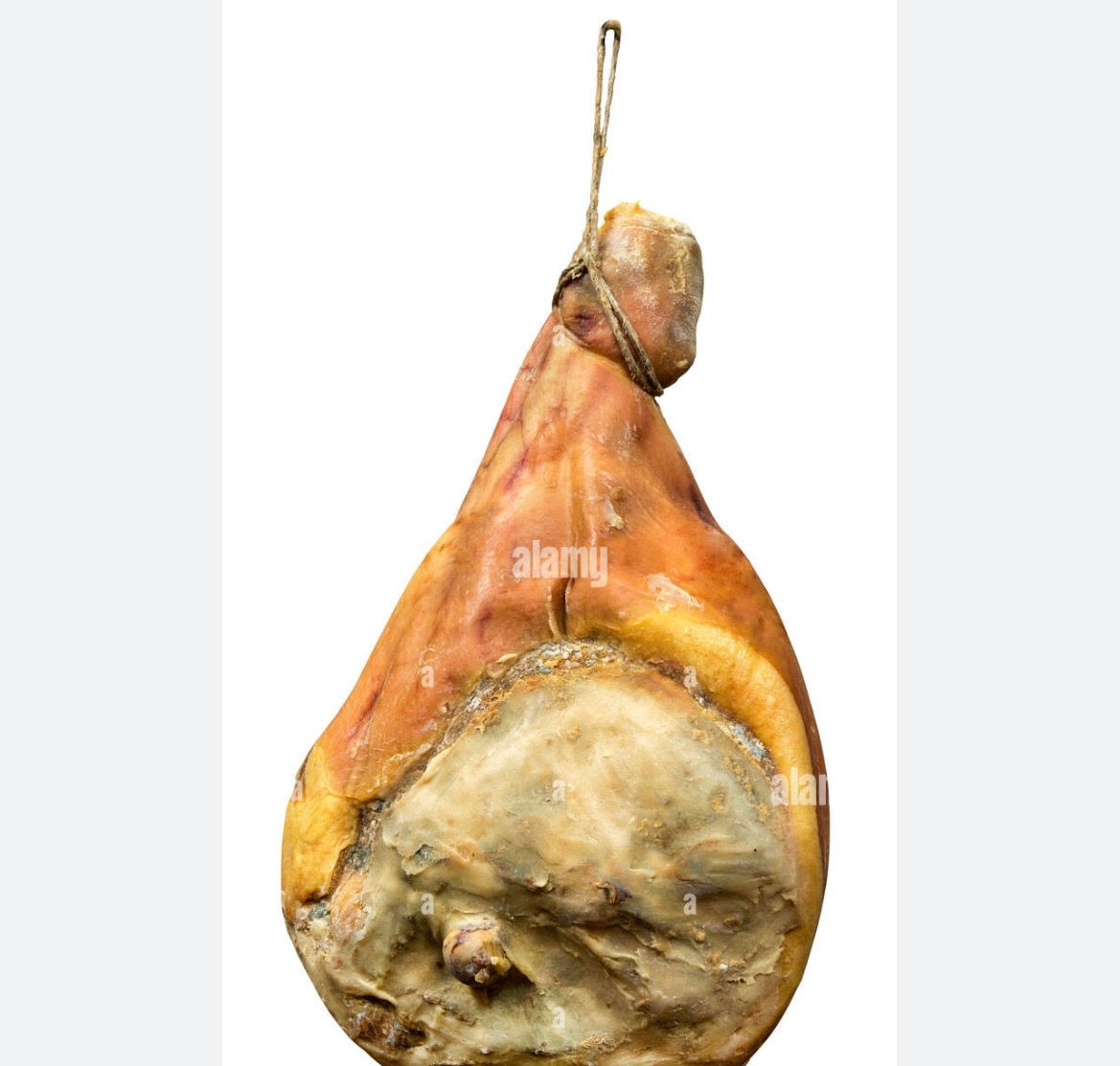

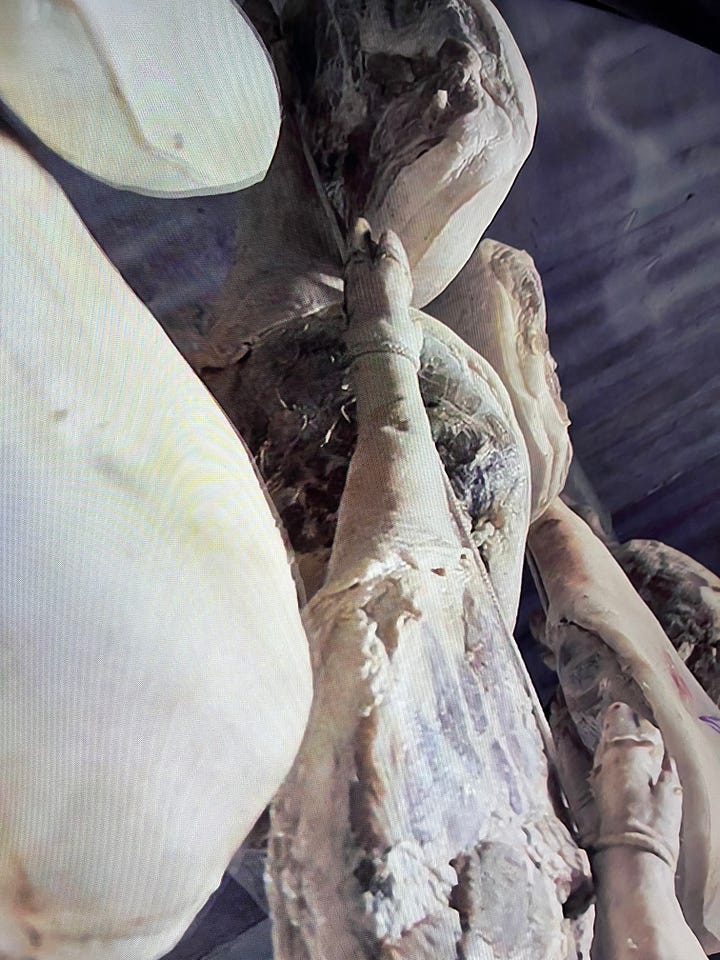

While there are as many ways to hang a ham as there are ways to skin a cat, I have not found any practice that uses the hamstring tendons. Most ham-makers, from Spain to China, simply tie a rope around the animal’s ankle or foot (see the photos from Jinhua, China above). In northern Italy, speck is often deboned and hung with hooks or strings that run directly through the meat. In other parts of Italy, makers of prosciutto hang the ham by removing the animal’s foot but keeping some of the ankle bones attached. A string tied around the lower leg gets caught on the bulbous ankle bone so it doesn’t slip off.

These days, many Americans hang hams in a fabric stocking, which allows air flow and moisture drainage. A stocking also lets the ham hang ankle-down, which helps it form the teardrop shape that many Americans have come to expect from their hams.

So, does anybody use the hamstrings to hang a ham? Dr. Jim Chlebowski, a family doctor in central Pennsylvania who cures both patients and meat, learned from an Italian speck-maker to hang pig hindquarters using tendons ***but they are the animal’s Achilles tendon in back of the ankle, rather than the hamstrings in back of the knee.

So nobody really uses the hamstrings to hang a ham. Besides, it would ruin some of the thigh meat. So perhaps these tendons are called “hamstrings” simply because they are the strings associated with the thigh (or ham) muscles and not because anyone uses them to hang animal hams.

Have you ever cured a ham? How did you hang it?

References

Kurlansky, Mark. Food of a Younger Land: A Portrait of American Food from the Lost WPA Files. Riverhead Books, 2010. Pg 119.

Wonderful article! In Spain they often cure the front quarter as well as the hind because " the only thing a red blooded Spaniard likes more than 2 hams per pig is 4"

Great article.

I just cured some venison single muscle roasts and then pastramified them in the smoker.

I don't hang them, just liquid cure for 6 days in the fridge.